SHARED INTEL Q&A: Rethinking Zero Trust to close the widening gap on file-borne threats

For years, “Zero Trust” has reshaped cybersecurity architecture — pushing organizations to move beyond the perimeter and reframe everything around identity, access control, and segmentation.

Related: The Zero-Trust revolution

These shifts are overdue. But as the frameworks mature, a critical blind spot remains: files.

Spreadsheets, PDFs, Word docs — they flow freely across teams, vendors, clouds, and networks. Once a file clears antivirus, escapes sandbox scrutiny, or sidesteps an AI scan, it’s often trusted by default. That’s a problem.

Spreadsheets, PDFs, Word docs — they flow freely across teams, vendors, clouds, and networks. Once a file clears antivirus, escapes sandbox scrutiny, or sidesteps an AI scan, it’s often trusted by default. That’s a problem.

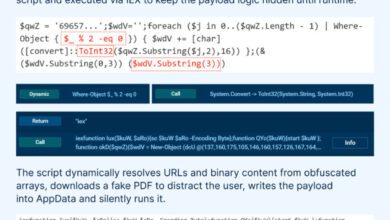

Today’s attackers aren’t sending obvious malware through the front door. They’re crafting polyglot files, embedding malicious code in image metadata, or hiding payloads in malformed XML and QR files — techniques designed to evade traditional detection entirely. Even machine-learning tools miss these threats more often than you’d think.

That’s why technologies like Content Disarm and Reconstruction (CDR) are gaining traction. Instead of detecting threats, CDR rebuilds files from the ground up — removing potentially harmful content and delivering safe, policy-compliant versions in real time.

In high-security environments like government and defense, CDR is already a requirement. Glasswall’s platform, for example, is mandated in NSA-approved cross-domain solutions. Yet in many enterprises — even those pursuing Zero Trust — file handling remains an afterthought.

To explore this gap, I spoke with Connor Morley, Head of Security Research at Glasswall, about how file risk continues to fly under the radar, the techniques that slip through, and how organizations can bring files into their Zero Trust fold.

LW: Why do files still get a free pass in most Zero Trust strategies?

Morley: The simplest answer is utility and business requirements. Several Zero Trust strategies focus on restricting the access and capabilities of an end-user or endpoint, with executable components being the highest priority. These restrictions are effective at limiting the scope of a breach, but they often rely on known, mature detection technologies to intercept the highest-level threats.

When organizations require the seamless transmission of mission-critical documents, adding additional checks can cause delays that are considered unacceptable. Some Zero Trust methods also flatten documents, fundamentally changing them in format and functionality, which can make them unusable for legitimate purposes. Add in the perception that internal training and existing detection tools are sufficient, and many deployments judge the risk of disruption to be higher than the risk of a malicious file slipping through.

Yet statistics show this is a dangerous trade-off: roughly 60% of breaches still originate from basic phishing or social engineering, and about 55% of those involve Office or PDF files.

LW: How have file-based attack techniques evolved?

Morley

Morley: Historically, document-based attacks have relied on a limited set of capabilities: VBA macros in Office documents, JavaScript in PDFs, and auto-script capabilities in archives. These methods are still extremely effective — so effective that attackers continue to use them today. The scripts can be simple or highly complex, sometimes standalone, sometimes part of multi-stage attacks with secondary payloads.

We also see advanced techniques emerging. These include exploiting specific vulnerabilities in rendering and processing systems, such as use-after-free flaws, or weaknesses in dependency libraries like TIFF image handling. Polyglot files, which combine multiple file formats, are still being used successfully for both active attacks and covert data smuggling.

LW: Why do detection tools — even AI-driven — struggle to catch these threats?

Morley: Traditional detection systems work extremely well against threats that are already known, using preset patterns or rules. AI models operate on the same principle, albeit in more advanced ways, but they can only detect threats similar to what they have seen before and been trained on. Unknown, new, or zero-day threats often go undetected.

In some cases, detection systems may not parse document files at all, treating them as opaque data blobs. They may detect known component hashes or specific rule-based strings but overlook advanced payloads that are deliberately designed to evade such detection. Attackers can embed malicious capabilities in a file under multiple layers of obfuscation, preventing any match to known patterns. Detection systems typically lack the ability to determine the context of a document, so they may miss anything but the most obvious threats.

LW: What makes cross-domain environments especially vulnerable?

Morley: Cross-domain environments, with differing security classifications, present high-value targets for file-based malware. When files move from low to high, there’s the risk of malware entering a sensitive network; when moving from high to low, there’s the risk of data exfiltration.

Files entering from a low-security domain may have passed initial checks but still contain risky elements. Before moving into a higher-security environment, these risks must be removed to prevent malicious components from being triggered. Going from high to low, the focus shifts to data loss prevention — removing any elements that could smuggle data, whether those are technical features or even standard document content. Because files crossing these boundaries can do serious harm, they require an elevated level of scrutiny.

LW: How should security teams rethink file handling in Zero Trust?

Morley: Zero Trust is about restricting access, minimizing risk, and assuming a breach is already in progress. When applying this mindset to file handling, we must assume that all files could be malicious. This requires filtering and sanitizing every file, regardless of origin, to remove elements that could be weaponized, as well as any malformations or abnormalities that could hide data or disrupt systems.

Blanket methods like file flattening — turning Word docs into PDFs — remove risks but also strip legitimate functionality. Instead, a targeted approach should assess each file in its original format, remove risky components, and deliver a safe, fully functional version to the user. This maintains both security and usability.

LW: What questions should boards or CISOs be asking about file risk?

Morley: I think there are two core questions. First: What is the scope of file-based risk across our industry? Second: Why does this risk persist despite being so well-known? These lead naturally to a third question: What can we do to prevent such attacks in the future?

The reality is that file-based attack vectors remain consistently and effectively used by adversaries, and existing security systems are not enough to stop them. User training is valuable but will never be 100% effective.

LW: What’s one common myth about file safety you’d like to dispel?

Morley: One of the biggest myths is that file-based attacks are obvious and easy to avoid. Many technical users think these threats can be spotted with minimal effort. While some campaigns are indeed easy to spot, others — especially those leveraging AI — can be highly targeted and deceptive.

Non-technical users continue to fall victim to phishing and watering-hole attacks, and modern techniques like SEO manipulation and AI-generated spear-phishing can trick even experienced users. The idea that file-based exploits are easy to detect is simply false. If that were the case, we wouldn’t still see about 60% of breaches originating from user-interacted malicious files.

File security will always be a challenge because attackers know how effective it is and will continue to evolve their tactics accordingly.

Acohido

Pulitzer Prize-winning business journalist Byron V. Acohido is dedicated to fostering public awareness about how to make the Internet as private and secure as it ought to be.

(LW provides consulting services to the vendors we cover.)

The post SHARED INTEL Q&A: Rethinking Zero Trust to close the widening gap on file-borne threats first appeared on The Last Watchdog.